セシル・浅沼=ブリス (訳:渡名喜 庸哲)

神奈川大学評論、12月、79号

二〇一一年三月一一日の東北地方での地震および津波、そして言うまでもなくそれによって引き起こされた原子力発電所の爆発から三年が過ぎた。それ以降、被災管理のための懸念の中心にあるのは、人々をどう管理するか、人々の移動をどう管理するかという問題だ。私たちは、同年の一二月に、住居部門における被害状況に加え、津波の被害ばかりでなく、福島県および隣接する県の一部にかなり広範囲に広がった放射能汚染の被害を受けた人々の移住体制についての詳細な報告を書いた[1]。政府は、一六万人が住居を移転し、そのうち一〇万人が県内に、六万人が県外に移転したとしている。今日では、大部分が汚染された土地で生活することになる帰還政策のために、一四万人が避難生活を送り、その内訳は同等の割合、すなわち、県内が一〇万人、県外が四万人である。しかしながら、これらの数字はきわめて厄介な登録システムの産物であって、それに従うことを望まない住民も無視しえない数いる[2]。したがって、移転した人々の数は、公的な統計が私たちに伝えるものよりもかなり多い。今日の日本で、原発避難者たちはどうなっているのか。世界規模の災害の管理を試みてきたここ三年にわたって、地方行政においてはこうした住民の保護のためにどのような政策がとられてきたのか。いまなおリスクがあるにもかかわらず、またあらゆる請願があるにもかかわらず、一部はいまだに汚染された地域に人々を帰還させることをめざすという当局側の動機はどのようなものなのか。以下では、部分的ではあるが、これらの点を明らかにすることを試みたい。

カタストロフのいくつかの争点

カタストロフということで私たちが述べたいのは、ジャン=ジャック・デルフールの定義にしたがって[3]、「生じたリスクについての軽視、過小評価、歪曲、それを検討することの拒否などの一連の現実的な要因の正常な帰結および、こうした要因が可視的になること」である。彼が述べるように、それは「厳密に人間的-技術的な因果系列」を示す。ここに認められるのは、「ある人の評判をすみやかに落とすには、機械を批判しているのではないかと疑われること以上のものはない」ということだ[4]。だが、避難移住に対する政府の管理を問題にするとき、またこの政府がこれについて行なった選択を理解できるようにするためには、その政策を内側からも外側からも理解することが肝要である。加えて、問題のカタストロフに続けて生じたもっとも大きな逆説のなかには、新たな原子力発電所の建設と、新たな方位(とりわけアジア)におけるその開発に向けて、フランスと日本(とりわけアレヴァと三菱)の原子力に関する国際的な合意が数を増しているというものがある[5]。さらに、もしかすると偶然の一致かもしれないが、三菱グループが二〇一四年六月にユーロサトリにはじめて参加したことも記しておくべきだろう。ユーロサトリとは、それを報じた新聞のお好みの表現を使えば、地上兵器に関する世界最大のサロンである[6]。

準備段階として、二〇一二年一二月に、福島にて、世界各国の代表者が集まり、いっそう安全で危険のない原子力発電所の開発を促進するための「原子力安全に関する福島閣僚会議」が開かれた[7]。原子力エネルギーを継続し、発展させるという政治的な決定がなされ、できるかぎり迅速な、そしてできるかぎりコストのかからないような帰還が必要だとされることになった。リスクをはらんだ状況における採算性の計算の土台として用いられているのは、国際放射線防護委員会(ICRP)が放射能防護に関して「集団積算線量という考え方および費用対効果分析」に基づいて練り上げた方策である。ICRPによれば、リスク管理は、人間の生活に対し保護措置を実施することに収益性があるかないかを決めるために、この保護措置のために生じるコストに関わることになる生活に対し経済的な価値を付与するような方程式に基づいている[8]。二〇一三年一一月に私たちがフランス原子力防護評価研究所(CEPN)所長でICRPの委員でもあるジャック・ロシャールとインタビューを行なった際に彼が述べたところによると、「エートスはタナトス〔フロイトの用語で死への欲動〕なしにはけっして進まない」のだ[9]。すべてが天秤をどちらのほうに傾かせたいかにかかっているということだ。人間の生活に金銭的な価値を付与することは、もちろんのこと、私たちの社会における(すでにモノとなっている)存在のさらなるモノ化の傾向をもっとも極限的に達成させるものである。

人口の流出をコントロールする政策については、私たちが以上述べてきたような文脈において日本政府の年間の優先課題計画に述べられている指針に従うと、次の三つの段階に区切ることができる。

あべこべの人口流出管理政策

第一の段階は、カタストロフに続く初年度に実施されたものである。緊急時の対応をとる必要があったため、とりわけ、被災者を受け入れるために国内で空家となっている公営住宅の無償開放がなされた。ほどなく、保護という幻想を作りあげることで、福島県内において安心感を与える試みがなされた。具体的で目に見える施策がいくつもなされた。

一部は汚染地域に建設されている仮設住宅、細工のされた測定器、すぐさま有効性について問題点の指摘された除染は、そのもっとも目に付く事例である。

二〇一二年の末には、国内で空家となっている公営住宅の無償提供について国レヴェルでの指示が停止されたことを通じ、最初の帰還の呼びかけがなされることになる。選択はそれ以降、地方自治体の手に委ねられることになった。ここに、今回の災害管理を特徴づける根本的なポイントの一つがある。それは、責任の所在を変えるということだ。公的な権力、とりわけ政府の責任から地方自治体の責任へというのがこのプロセスの第一段階である。このことは、復興計画がかなり遅れたという点にも表れている。関連する地方自治体はこれを引き受ける手段をもっていないためである。こうして、虚構の復興を推奨し帰還を呼びかけつつ復興をしないということによって、本来に復興政策を行なった場合に比してはるかに少ないコストでの維持が可能になるわけである。しかしとりわけ、当局は、統計的・科学的な追跡調査ができるようにと人々を福島県内に固定しておこうとしつつも、彼らを助かる見込みはないとみなしているため、その保護に資金を投じる心構えはもっていない。すでに住民が減り、さらにいっそう減るようになる県内において、どうして公営住宅に資金を投じようか。

国家による責任転嫁の第二段階は、個々人に責任を負わせることにある。個々人は、汚染された環境で自分の生を管理しなければならなくなり、あるいはまた避難の選択が不可能となったことに直面しなければならなくなる。実際的には、政府は、希望する者に避難ができるようにするような経済的ないし物質的な支援をまったく提案していない。道徳的には、日本人は故郷を離れることができないという、あらかじめこしらえられたイメージを広く伝播させることで、避難を断念させることを目ざすような情報戦略が練り上げられる。自分の一生をはぐくんできた土地であればなおさらそこを離れることが強い悲痛をもたらすというが明白だとすれば、こうした感情は日本人に固有のものではないだろう。その上、私たちが研究の際にインタビューを行なった多くの人々は、自分の住む土地への愛着にもかかわらず避難したいという願いを口にしていた。彼らは、、こうした願いを実践に移すことが物質的に不可能であるという事態に直面していたのである[10]。

回復をめざした再開

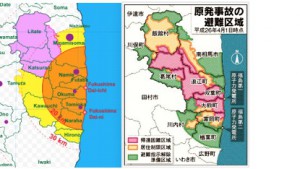

こうした帰還を呼びかける政策は、二〇一三年五月末になされた一部区域の開放に帰着した。二〇一一年四月、政府は双葉町ほか八つの地方自治体を含む二〇キロ圏内を避難指示地域に設定した。その区域の全体が再編成され、「避難指示解除準備区域」(放射線量は二〇ミリシーベルト以下)、「帰還困難区域」(五〇ミリシーベルト)に見なおされた。原子力発電所周辺の九つの地方自治体を含む特別警戒区域はすべてなくなることになった[11]。この施策の影響を受ける住民は76,420人である。そのうちの67%、すなわち51,360人は、避難指示解除準備区域におり、自分の住居の保全のために日中のあいだは自由に移動することができるようになった。避難指示の解除は部分的には二〇一四年にもなされている。住民の25%(19,230人)に関わる居住制限区域は、労働許可がなくとも日中は自由に出入りできるようになった。日中にそこに働きに来ることのできる人数は、人口の42%、すなわち32,130人である。

しかしながら、同じ自治体内でも状況はさまざまである。スーパーマーケット、ケア・センターなどのサーヴィスはまだ機能していない。大熊町や双葉町の一部は、避難指示解除準備区としての開放を見込んで、除染試験区域として利用されている。

二〇一四年一月時点の避難区域の状況[12]

二〇一四年一月時点の避難区域の状況[12]

富岡町の居住制限区域(二〇一三年一〇月二五日) 放射線量は毎時三マイクロシーベルト。(写真は筆者)

富岡町の居住制限区域(二〇一三年一〇月二五日) 放射線量は毎時三マイクロシーベルト。(写真は筆者)

保護幻想による従属:「たくましくあれ!」

人口流出をコントロールしようとする政策の第二段階は、いくつかの概念装置、とりわけレジリエンスという概念の使用に現れる。二〇一二年の科学技術白書は、「強くたくましい(resilient)社会の構築に向けて」と題され、その旗色を告げている。こうして、非常に幅広い領域においてこの概念を検討したり活用したりする研究に研究予算が向けられることになった。この概念は、英語のレジリエンシー(resiliency)から来たもので、科学の領域ではまずは材料物理で用いられ、ある物体が衝撃を受けた後にもそのもともとの形態を取り戻すことができるという柔軟性を示すものであった。エミー・ワーナーが子どもがトラウマを克服するのに役立ったいくつかの要因をつきとめることによって、この概念は心理学に導入された。この概念をフランスで普及させたのは、ボリス・シルルニックである。災害を扱うリスク学では、今日この概念は、都市が災害に持ちこたえることができるようなモデルを規定するために用いられている。都市は、不測の事態に対し自らの脆弱性を認めつつ、多様な自然的ないし人為的なリスクを消化吸収できるためにレジリエントな特性を採用する必要があるとされる[13]。目下のケースでは、こうした方策がすべて用いられ、心理学的、経済学的、都市工学的等々のさまざまなレジリエンスに関わる応用アプローチが柔らかく混ぜられ、危険を前にした不安という原初的な感情にいまだに縛られている人々に対して逃げるのはやめるよう示唆するために誇示されているのである。とはいえ、原子力のカタストロフの場合にレジリエンスについて語ること、それは、自分の身を守るための振る舞いの原動力たる恐怖がしばしば有益であるという事実を軽んじることである。

都市工学のレジリエンスを災害管理の手段にすることはさらに問題を生じさせる。土地と空間を創り出す人々のあいだの乖離がいっそう広がることである。都市を対象と見つつ、しかし同時に、自律的な生きた存在という意味での主体ともみなすような説明には、存在が不在となる。都市は、支えたり、あるいは世話をしたりする対象とされるが、しかしそれはただ人間が創り出したものでしかないということは鑑みられることもない。このことが生み出す本質的な問題は、ここでもまた、人間存在の行動が環境に及ぼす影響に関する責任転嫁にある[14]。空間を創り出し管理する行為者、そうした土地のなかに生きる者という存在が抹消され、生活の場所、環境、住んでいる人々、それを創り出したり、管理したりする人々――後の三つは同時に務めることができる――のあいだの相互作用がなくなってゆくのである。たとえば、災害防護の任を担う福島大学の専門家は、二〇一四年六月に行なったインタビューで、地震の際に日本人はレジリエンスが上手だと述べていた。彼はこの見解をスライドに図式化して示してくれたが、そこには次のような均衡が描かれていた。天秤の一方には、レジリエンスを表す重い丸があり、他方には災害を示す軽い丸がある。こうしたイメージに従うと、レジリエンスが重くなればなるほど、災害の効果は軽くなることになる。私が彼にこのことは具体的にはどういうことを意味するのかと尋ねると、彼は当惑しつつ、このインタビューの三日目にマグニチュード四の地震があったがこの地震がこうした概念にも勝るものであったと答えてくれた。「私たちにとって、今や、道路を拡げることで、避難経路を確保することができます。二〇一一年のような渋滞は新たな災害が起きても起こることはないでしょう。というのも、原子力発電所はまだ安定していませんが、そのふもとまで道路は再開しているからです」。科学と良心とのあいだで目下いっそうの隔たりが広がっているが、それを縮める必要性を示す事例としては、これ以上明白なものはないだろう。

レジリエンスからリスク・コミュニケーションへ

人口移動に対するコントロールの第三段階は、リスク・コミュニケーションに依拠することである。これについては毎年一歩ずついっそうの抽象化が行なわれている。国は、避難者が故郷から離れることで心理的な苦痛を受けているといって、絶えず帰還への呼びかけを続けている[15]。福島県立医科大学および国際原子力機関(IAEA)の専門家らが二〇一三年一一月二一日から二四日に集まり国際会議を開催したが、それによると、とりわけ仮設住宅や汚染されたと「感じられる」地域に住む人々において観察される神経系の不調は、なかでも過剰な防護によるとされている。たとえば、福島県立医科大学の神経精神医学講座教授の増子博文氏によれば、マスクの着用、学校の校庭やプールの使用や食べ物に関するさまざまな制限などは、とりわけ精神疾患の素質をもった人にとっては心理的な変調の元になるストレスを引き起こすものとされる。だが、こうした精神衰弱が、汚染された地域から逃れることができないということの帰結かもしれないという可能性についてはまったく言及はなされなかった。

当事者に情報を伝え市民の信頼を取り戻すという目的のもと、二〇一四年には二億円を超える特別予算がついて、真のコミュニケーション戦略が採択された[16]。この強力な政策が目指すのは、福島県の小学校児童に向けた放射線や癌に関するワークショップの開催[17]や汚染された環境での生活管理を学ぶ教材の配布などを通じて、より安心した生活を送るために健康リスクについて「教育する」ことである[18]。これこそ本来の意味での教化戦略と言えるだろう。つまり、教説を受け容れることが必要とされ、それ以外はありえない、という戦略が適用されることになったのだから。

福島の小学校で二〇一四年三月二九日に行なわれたキッズキャンサーセミナーのチラシ[19]

福島の小学校で二〇一四年三月二九日に行なわれたキッズキャンサーセミナーのチラシ[19]

死者数の再上昇を懸念する政府

東京電力福島第一原子力発電所の爆発事故に関連する死者数は、二〇一四年九月一一日現在で一一七〇人を超えている[20]。本来なら仮住まいとなるはずの住居に移り住んだ高齢層が最初にその被害を受けることになった。国連の特別報告者のアナンド・グローバー氏が、二〇一二年一二月一五日から二六日にかけての日本での調査を受けて国連人権理事会で報告をしたにもかかわらず[21]、避難の権利が与えられることがなかったため、住民が期待していた移住に対して経済的な支援がなされることはなかった。彼らの健康状態は日に日に悪化してゆき、日々の管理しがたい不安定な環境を前にして、自費での出発を決める者もでてきた。一部では、うつ病やアルコールなどにより貧困化のスパイラルに陥る者もいる。汚染水のコントロールがいまだにできていない第一原発に隣接する自治体ごとの死者数の分布を見ると、浪江町は三三三人、富岡町は二五〇人、双葉町は一一三人、大熊町は一〇六人であり、これらの自治体の全住民のうち八〇二の死者数が原発事故による帰結として数えられる。そのうちの五五人は、この半年のうちに記録されたものだ。福島民報は二〇一四年七月二一日の記事で自殺者数が再び上昇しているという内閣府の発表を報じ警鐘をならしている[22]。

甲状腺癌の増加、あるいは専門家たちの争い

甲状腺癌の数の増加もまた、原発事故の健康に対する影響の一覧のなかに入れねばならない。二〇一四年八月二四日に公表された福島県による調査では、一八才以下の子どもの被験者三〇万人のうち一〇四人の子どもが甲状腺癌にかかっていると診断された[23]。

こうした癌は原発事故の帰結ではないという福島県の調査を行なった専門家らの見解に対して、日本の内外の疫学研究者から反対の声が発せられている。福島県の専門家は、甲状腺癌の増加はスクリーニングによるものとする。つまり、現在の放射線測定装置は改良を重ねており、いっそう正確に病気を検出できるようになってきているため、過去のデータとの比較は難しいとしている。環境省も、できるだけ早期の帰還のための避難地域の再開および二〇一四年九月から一〇月に予定された二つの原発再稼働をめざし、住民たちに精神的な安心を与えるためにこれと同じ論理を用いている。二〇一四年八月一七日、政府のインターネットテレビ[24]、五つの全国紙および二つの地方紙を通じ広報を出し[25]、年間一〇〇ミリシーベルト以下では、健康について目立った影響はないとした。政府による最初の報告はすでに二〇一四年二月に公表されているが、そこにも年間一〇〇ミリシーベルトの環境では低線量の環境と同様に健康への危険が弱いと明記されている[26]。疫学を専門とする岡山大学の津田敏秀教授は、福島県立医科大学の調査が誤っているのではないかとし、一点ずつ検討した結果を公表している。津田教授によれば、一方で、二〇一三年の世界保健機関(WHO)の報告は明白に福島で癌にかかる数が現在増加しており、今後も増加するとしており[27]、他方で、科学的に見ると、年間一〇〇ミリシーベルト以下に健康への影響がないとする日本政府の立場は、それをあえて支持する外国の疫学の専門家はほとんどいないような錯誤であるとされる[28]。疫学研究者で東フィンランド大学のキース・ベーヴァーストック教授は、かつて世界保健機関の委員も務めていたが、原子放射線の影響に関する国連科学委員会(UNSCEAR)への公開質問状において、二〇一三年のUNSCEAR報告に示された結果を批判している[29]。彼によれば、この報告は、それが基づいている調査から三年を経てようやく公表されたが、それはこの委員会の委員のあいだで対立があったためである。委員の一人ウォルフガング・ヴァイス博士は、福島での原発事故と癌の増加との関連を否定することを結論づけたこの報告にとりわけ反対していたのだ。とはいえ、この報告書は、事故がまったく収束していないことは否定していない。というのも、東京電力の発表(二〇一四年五月)にあるとおり、放射能はいまも原子量発電所から太平洋や大気中に流出しているのだ[30]。

移住に対する処方箋としてのコミュニケーション

こうした専門家間の対立を前に、いっそう直接的なしかたで議論を打ち切ろうとする専門家もいる――ただし彼らは世界保健機関(WHO)、国際原子力機関(IAEA)、国際放射線防護委員会(ICRP)など同じ組織に属している。このことがとりわけ見られたのは、福島県立医科大学と笹川記念保健協力財団が共催した、福島での第三回国際専門家会議においてである。会議の標題、「放射線と健康リスクを超えて~復興とレジリエンスに向けて~」は、疫学的な議論が乗り越えられ、レジリエンスと復興の促進を目指す山頂にたどり着いたことを告げていた。

アルゼンチンの環境科学・海洋科学アカデミーの会員で、UNSCEARやIAEA安全基準委員会委員も務めるアーベル・ゴンザレス氏にとって、すべてはコミュニケーションの問題である。保護にはコストがかかること、人口の一部分を避難ないし移住させることは目標にはなりえないことを何度も指摘した後で、彼は言葉の問題に触れるべきだとした。とりわけ、彼によれば、住民の懸念は「被ばく」という言葉使いによるものである。この語は、病理学的な言葉であり、放射線は太陽光からもやってくるのに、被ばくに対し否定的なイメージをあまりにも付与してしまうというのだ。WHOのエミリー・バン・デベンターも同じ考えを述べているが、彼女はさらに小学校児童にも基本的な知識を教えるために太陽光についてと同様に被ばくについてもワークショップを開くべきだと提案し、こう結論づけている。「いずれにしても、私たちはコスト・ベネフィット〔費用便益〕の賭けに勝たねばなりません」。そのために、そしてまた明らかに確認される人口流出を止めるためには、安心感を創り出すということが今後の課題となる。この課題を引き受けるというのが国際放射線防護委員会(ICRP)のジャック・ロシャールであるが、彼はそのために、とりわけ「住民に対し、彼らの日常の一部をなす被ばくというこの新たな要素を受け容れてもらう」と言う。彼らはみな、住民の内部被ばくを測定するのに十分なデータはないということについては了解しているのだが、いずれにしてもそれは懸念すべき事柄のうちには入らないようだ。ロシャールによれば、重要なのは、閾値を設定することではなく、「個別的な手段によるチェルノブイリのような手本に基づいた避難というプロセスをやめることで人々に安心を取り戻し、汚染された環境のなかで日常生活の自己管理をできるようにする」ことである。そのために彼は、二〇一三年一一月二一日から二四日の福島県立医科大学と国際原子力機関(IAEA)共催の第二回シンポジウムの出席者でイスラエル保健省のイシェイ・オストフェルドが提案した方法を用いようとする。オストフェルド氏によれば、「イスラエルは一般に、テロに対する医学的な対処をモデルとして用いている。それゆえこの経験は、放射能のテロの領域においても役立ちうるだろう」[31]。ロシャールの提案はつまり、イスラエルで戦争中に用いられる技術でもってレジリエンスに到達できるようにするということである。すなわち、県内に散らばったすでに会得済みの住民たちからなる小さなグループを組織し、彼らに近くにいる人々たちを安心させる任を負ってもらうということだ。この作業は、ICRPによってエートス福島のワークショップや対話集会を通じてすでに福島で実施されており、その第九回目の会合が二〇一四年八月に実施された。

そこに働いている論理は、つまるところ、社会的な保護のために公的な手段でもって災害後の保護を実施するということではなく、それを政治的決定に資するように合わせてゆくというものである。それはまったく陰謀のようなものではない。それは、原子力カタストロフという文脈において、自国の領土で原子力産業を継続してゆくために国家が採用した移住避難管理計画を適用するということである。それでもやはり、世論を際限なく操作することができるという自分たちの心理的な公準の価値を固く確信した専門家たちは、以上の現状把握によって私たちの目に明らかとなった不気味な帰結を前にして、そこに自分たちの似姿を見るのではないのかと問うことはできるだろう。

著者紹介:セシル・浅沼=ブリス 専門は都市社会学。リール第一大学社会学・経済学研究所(Clersé)および日仏会館客員研究員。二〇〇一年より日本在住。福島原発事故の管理について多くの論文を執筆し、日仏において同テーマに関する多くのシンポジウムの参加者および主催者を務める。主なものとして以下がある。

- 二〇一四年 シンポジウム「福島原子力災害のあとさき:不可能な逃避?」共催および原子力災害後の生活条件についてのドキュメンタリー映画『がんばろう!』上映会(六月一三日、東京、日仏会館)

- 二〇一四年、シンポジウム「福島原発事故後、健康への権利をどう実現できるか?:その現状と見地」A・ゴノン、T・リボーとの共催(三月二二日、京都、同志社大学)

- 二〇一三年三月、論文「フクシマ、苦悩する民主主義」(仏語)(Revue Outre terre – Revue Française de géopolitique)

- 二〇一三年一〇月、インタビュー「フクシマへの帰還」(Interview France Culture, émission Terre à Terre par Ruth Stegassy)

- 二〇一三年三月八日、「忘却から記憶へ 復興への抵抗形態」(東京大学での大震災後の文化的記念対応)

- 二〇一三年、シンポジウム「フクシマにおける保護と服従」T・リボーとの共催(一〇月一五‐一六日、東京、日仏会館)

- 二〇一三年、「市民の責務に直面した学問的論争」、フランス国立科学研究センター・学際ミッションPEPS(学問・社会間の評価、論争、コミュニケーション)学術責任者。

- 二〇一二年、シンポジウム「市民科学者国際シンポジウム」共催(福島県猪苗代町、六月二三-二四日)

- 二〇一二年、「完全に脆弱な状況下で、いかなる人命保護が可能か? フクシマの震災における居住と県内移住」、フランス国立科学研究センター・学際ミッション「原子力、危険性、社会」プログラムをT・リボーと学術共同責任者として開催

- 二〇一一年一一月、論文「日本における国共住宅――2011 年 3 月 11 日の危機後の状況」(仏語)(Revue Urbanisme)

[1] C.ASANUMA-BRICE (2011), « Logement social au Japon : Un bilan après la crise du 11 mars 2011 », Revue Urbanisme, Nov.

[2] C.ASANUMA-BRICE et T. RIBAULT: Quelle protection humaine en situation de vulnérabilité totale ? – Logement et migration intérieure dans le désastre de Fukushima – Rapport dans le cadre du programme Nucléaire, risque et société de la Mission Interdisciplinarité du CNRS (2012).

[3] J.-J.DELFOUR (2014) : La condition nucléaire, réflexions sur la situation atomique de l’humanité, Paris, éditions L’échappée.

[4] ギュンター・アンダース『時代おくれの人間』(一九五六年)〔法政大学出版局、一九九四年〕。

[5] とりわけ『ルモンド』二〇一三年五月二日の記事「三菱‐アレヴァのデュオがトルコに四つの原子炉を建造予定」および『パリジャン』二〇一三年一〇月二六日の記事「原子力――アレヴァ、モンアトム、三菱のパートナー協定」を参照。

[6] 「日本が武器販売競争に復帰」、『ルモンド』二〇一四年六月一六日。

[7] 二〇一二年一二月一五日から一七日にかけて、福島県において、原子力安全に関する福島閣僚会議が開催された。

[8] F. ROMERIO (1994) : Energie, économie, environnement : Le cas de l’électricité en Europe entre passé, présent et futur, Genève, Librairie DROZ.

[9] このインタビューは、二〇一三年一一月に福島でT・リボーとともになされた。J・ロシャールがここで言及しているエートスというのは、一九八六年にチェルノブイリで設立され、福島でも二〇一二年に設立されたプロジェクトで、汚染された地域に住む人々に放射線防護の知識を与えることを目的としたものである。それは、われわれがここで問題にしている責任転嫁、つまり放射線防護の自己管理のためである。

[10] C.ASANUMA-BRICE (2013), « Fukushima, une démocratie en souffrance », Revue Outre terre-Revue Française de géopolitique, Mars.

[11] 『読売新聞』二〇一三年五月九日。「政府の原子力災害対策本部は7日、東京電力福島第一原発事故で福島県双葉町の全域に設定されていた原則立ち入り禁止の「警戒区域」を今月28日午前0時に解除すると決めた」。

[12] 「事故後一〇年全て二〇ミリシーベルト未満 帰還困難区域除染後の線量 国が試算」、『福島民報』二〇一四年六月二三日。

[13] G. Djament-Tran, M. Reghezza-Zitt (2012), Résiliences urbaines Les villes face aux catastrophes, ed. Le Manuscrit.

[14] この責任転嫁は、どのような責任の明確化にも必要となる都市における生産部門や社会実践の行為主体のあいだの連携が断絶していることによる。J・トロントによれば、「責任(responsabilité)という用語は〔…〕、「応答(réponse)という考え、つまり明らかに合理的な態度に依拠している」(Carol Gilligan, Arlie Hochschild, Joan Tronto, Contre l’indifférence des privilégiés, Payot. 2013, p. 103)。

[15] 『福島民報』二〇一三年一〇月一〇日「避難長期化で自殺増 県内1~8月 被災3県で最多15人 古里離れストレス」。「東日本大震災と東京電力福島第一原発事故に関連する県内の自殺者が増加傾向にあることが内閣府のまとめで分かった。今年は8月末現在で15人に上り、昨年1年間の13人、一昨年の10人を既に上回っている。岩手県の5倍で被災3県で最も多い。専門家は古里を離れての避難の長期化が精神的な負担を増大させていると指摘。増加傾向に拍車が掛かる懸念があり、対策が急務となっている。」

[16] 第三四回原子力委員会資料第六号「平成二六年度原子力関係経費概算要求額総表」。

[17] 第五二回日本癌治療学会学術集会「キッズキャンサーセミナー 福島でこそ日本一のがん教育が必要だ!」

[18] NHKの二〇一四年六月一〇日の報道によれば、「“放射能と暮らす”ガイド」が各自治体に配布された。

[19] http://congress.jsco.or.jp/jsco2014/index/page/id/83

[20]「原発関連死、一一〇〇人超す 福島、半年で七〇人増」、『東京新聞』二〇一四年九月一一日。

[21] Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Anand Grover, ONU, Mission to Japan (15- 26 November 2012).

[22]「関連死で自殺歯止めかからず 福島県内」、『福島民報』二〇一四年六月二一日。

[23]「甲状腺がん、疑い含め一〇四人 福島の子供三〇万人調査」、『朝日新聞』二〇一四年八月二四日。

[24] 中川恵一(東京大学医学部付属病院准教授)による講演(http://nettv.gov-online.go.jp/prg/prg10283.html?t=115&a=1)。

[25] 二〇一四年八月一七日に「放射線についての正しい知識を」という政府広報が、朝日新聞、毎日新聞、読売新聞、産経新聞、日経新聞の大手五紙と、福島民報と福島民友の地方紙二紙に掲載された。

[26] http://www.reconstruction.go.jp/topics/main-cat1/sub-cat1-1/20140218_basic_information_all.pdf

[27] 世界保健機関(WHO)の二〇一三年の「健康リスク評価」を参照。

[28] 津田敏秀「100msvをめぐって繰り返される誤解を招く表現」、『科学』、岩波書店、2014年5月、534-530頁。

[29] Keith Baverstock, « 2013 Unscear Report on Fukushima : a critical appraisal » (24 August 2014).

[31] Conference Program, International Academic Conference : Radiation, Health, and Society : Post – Fukushima Implications for Health Professional Education, 21-24 nov. 2013, p. 79.

Au-delà du réel –ou- Quand le concept participe de la création d’un espace idéal illusoire : de la gestion des flux migratoires par un Etat nucléariste dans un contexte de catastrophe nucléaire

Trois années se sont écoulées depuis le tremblement de terre suivi d’un tsunami le 11 mars 2011, qui, faut-il le rappeler, a engendré l’explosion d’une centrale nucléaire dans le nord-est du Japon. Dès lors, au cœur des préoccupations de la gestion des dégâts, se trouve celle des hommes et de leur mobilité. Nous avions, en décembre de la même année, rédigé un bilan précis des dégâts dans le secteur du logement, ainsi que du système de relogement des personnes victimes à la fois du tsunami, mais également de la contamination nucléaire qui s’est très largement répandue dans une partie de la région de Fukushima, et des départements voisins[1]. Le gouvernement a fait état de 160 000 personnes déplacées, dont 100 000 à l’intérieur du département et 60 000 à l’extérieur. Suite à la politique publique de retour à vivre dans les territoires en grande partie contaminés, l’estimation officielle est aujourd’hui de 140 000 personnes réfugiées, dans des proportions équivalentes : 100 000 à l’intérieur du territoire et 40 000 à l’extérieur. Néanmoins, ces chiffres sont les fruits d’un système d’enregistrement extrêmement contraignant, auquel une partie non négligeable des habitants n’a pas voulu se plier[2]. La population déplacée est donc notablement plus élevée que les statistiques officielles ne nous le laissent entendre. Qu’en est-il aujourd’hui des réfugiés du nucléaire au Japon ? Quelle politique locale de protection des habitants a été mise en place au cours de ces trois années de tentative de gestion d’un désastre mondial ? Quelles sont les motivations des autorités visant à contraindre la population au retour dans des zones, pour partie encore contaminées, en dépit du risque toujours présent, et contre toute requête ? Tels sont les quelques points que nous tenterons d’élucider en partie dans ce dossier.

Les enjeux de la catastrophe

Par catastrophe, nous désignerons ce qui, selon la définition de Jean-Jacques DELFOUR[3], « est l’effet normal d’une série de causes réelles et la mise en visibilité de cette série, c’est à dire des négligences, minimisations, contournements, refus de considération des risques créés». Comme le rappelle le même auteur, cela désigne « une série causale strictement humaine-technique ». Nous assumons ici le fait que «rien ne discrédite plus promptement un homme que d’être soupçonné de critiquer les machines »[4]. Mais il est essentiel, lorsque l’on évoque la gestion des flux migratoires par un gouvernement et afin de pouvoir comprendre les choix effectués par celui-ci, d’en appréhender la politique tant intérieur qu’extérieur. En outre, parmi les plus grands paradoxes qui ont suivi la catastrophe dont il est question ici, se trouve la multiplication des accords internationaux en matière de nucléaire entre la France et le Japon (Mitsubishi et Areva notamment) pour la construction de nouvelles centrales nucléaires et l’exploitation de nouveaux gisements[5], plus particulièrement en Asie. On notera, par ailleurs, mais c’est sans doute une coïncidence, la première participation en juin 2014 du groupe Mitsubishi à Eurosatory, le plus grand salon mondial de l’armement terrestre, comme aiment à le rappeler les journaux qui en font état.[6]

Dans une phase de préparation, en décembre 2012, s’est tenue à Fukushima La conférence ministérielle sur la sécurité nucléaire[7], réunissant des représentants des pays du monde entier, afin d’y promettre le développement de centrales désormais sûres et sans danger. La décision politique de poursuivre et de développer l’énergie nucléaire était prise, engendrant la nécessité d’un retour à la normale des plus prompts et à moindre coût. Les outils élaborés par l’ICRP (International Commission on Radiological Protection) en radio-protection, basés sur « les notions de doses collectives et sur les analyses coûts-bénéfices » sont utilisés comme fondement des calculs de profitabilité en situation de risque. Selon l’ICRP, la gestion du risque relève d’une équation attribuant une valeur économique à la vie humaine qui devra affronter le coût engendré pour sa protection afin de déterminer la rentabilité ou non de la mise en place de cette protection.[8] Comme le déclarait Jacques Lochard, membre du comité de l’ICRP et directeur du CEPN (centre d’étude sur l’évaluation de la protection dans le domaine nucléaire) lors d’un entretien que nous avons mené en novembre 2013, « Ethos ne va jamais sans Thanatos »[9]. Le tout est de savoir de quel côté l’on souhaite faire pencher la balance. Attribuer une valeur monétaire à la vie humaine matérialise certainement l’aboutissement le plus extrême de la tendance à l’objectivation de l’être (devenu objet) dans nos sociétés.

On peut découper en trois phases la politique de contrôle des flux de population en fonction des directives énoncées via les plans de priorité annuels du gouvernement japonais dans le contexte que nous venons de décrire.

Une politique de gestion des flux à rebours

La première étape a été mise en œuvre dans l’année qui a suivi la catastrophe. Il fallait répondre à l’urgence, et cela a été fait notamment par l’ouverture à la gratuité du parc de logements publics vacants sur l’ensemble du territoire afin d’y accueillir les victimes. Hâtivement, la tentative de réconfort prend place à l’intérieur du département de Fukushima, par la construction de l’illusion de la protection. Des mesures concrètes et visibles sont réalisées.

Les logements provisoires sont bâtis en partie sur des zones contaminées, l’installation des postes de mesure trafiqués et la décontamination, dont l’inefficacité a été rapidement remise en cause, sont les plus flagrantes.

|

Répartition des logements provisoires d’urgence + Répartition de la radioactivité (16 810 unités de logement) source : département de Fukushima) |

Carte réalisée par Cécile Asanuma-Brice

Carte réalisée par Cécile Asanuma-Brice

Logements provisoires de Aizuwakamatsu, Mai 2013

Logements provisoires de Aizuwakamatsu, Mai 2013

Photos Cécile Asanuma-Brice

La fin de l’année 2012 marque le premier appel au retour via l’arrêt de la décision nationale de gratuité des logements publics vacants sur l’ensemble du territoire, dont le choix est désormais remis entre les mains des collectivités locales. Voici un des points fondamentaux qui caractérise la gestion du désastre, à savoir le déplacement de la responsabilisation. Déresponsabiliser les pouvoirs publics plus particulièrement gouvernementaux au profit d’une responsabilisation des collectivités locales est le premier degré de ce processus. Cela se traduit par un retard considérable dans les plans de reconstruction, les collectivités locales concernées n’ayant pas les moyens de l’assumer. Ainsi, ne pas reconstruire tout en appelant au retour en ventant une reconstruction fictive, garantit un maintient des coûts à un niveau bien moindre comparé à celui des dépenses qu’impliqueraient de véritables politiques de reconstruction. Mais surtout, les autorités, qui travaillent à la fixation des populations dans le département afin d’assurer leur suivi statistique et scientifique, ne sont pas prêtes à investir pour protéger ces populations qu’elles estiment condamnées. Pourquoi investir dans des logements publics pour un département déjà dépeuplé et amené à l’être encore plus ?

Le second échelon vers une déresponsabilisation de l’Etat amène à faire peser la responsabilité sur les individus qui se voient contraints à la gestion de leur vie dans un environnement contaminé, ou encore confrontés au choix rendu impossible du refuge. Pratiquement, le gouvernement ne propose aucune aide financière ou matérielle afin de permettre aux gens qui le souhaiteraient de se réfugier. Moralement, une politique offensive de communication est élaborée via des images préconçues et largement véhiculées de l’impossibilité des japonais de quitter leur pays natal visant à motiver l’abandon du départ. S’il est évident que l’éloignement de sa terre est un déchirement d’autant plus fort lorsqu’il s’agit de celle que l’on a cultivé le temps d’une vie, ce sentiment n’est pas propre au peuple japonais. Par ailleurs, nombre des personnes que nous avons interviewées lors de nos recherches, ont exprimé leur désir du refuge malgré leur attachement à la terre, mais elles étaient confrontées à l’impossibilité matérielle de pouvoir mettre en œuvre leur désir.[10]

Rouvrir pour mieux guérir

Cette politique d’appel au retour se solde par la réouverture d’une partie de la zone à la fin mai 2013. En avril 2011, le gouvernement avait fixé une zone d’évacuation de 20 km comprenant la ville de Futaba et 8 autres collectivités locales. La totalité du périmètre est réorganisée. La zone de retour possible après décontamination 「避難指示解除準備区域」 (dont le taux de contamination était en deça de 20 millisievert), la zone de retour « confuse »「帰還困難区域」(50 millisievert) ont été revues. La zone de règlementation spéciale qui recouvrait les 9 collectivités locales autour de la centrale est totalement supprimée.[11] Une population de 76 420 personnes est concernée par ces mesures. 67% d’entre eux, soit 51 360 personnes, se trouvent dans la zone de « préparation à l’annulation de la directive d’évacuation » 避難指示解除準備et peuvent se déplacer librement dans la zone durant la journée afin d’entretenir leur habitat. L’ annulation de la directive a été effective en partie en 2014. La zone de restriction de résidence居住制限両区域 qui concerne 25 % des habitants (19230 personnes) , permet l’entrée et la sortie libre dans la journée, sans autoriser d’y travailler. La possibilité de revenir travailler dans la journée concerne 42% de la population soit 32 130 personnes.

Néanmoins, les situations varient à l’intérieur d’une même collectivité. Les supermarchés, centres de soins et autres services ne peuvent pas être remis en fonction. Une partie des villes de Okuma et Futaba sont utilisées comme zone test de décontamination, dans la perspective de rouvrir au retour la zone de préparation à l’annulation de la directive.

Carte de la situation de la zone d’évacuation au 1er avril 2014[12]

La ville de Tomioka dans la zone de résidence limitée, le 25 octobre 2013. Taux de radiation à 3 µSv/h.

La ville de Tomioka dans la zone de résidence limitée, le 25 octobre 2013. Taux de radiation à 3 µSv/h.

Photo : Cécile Asanuma-Brice

Soumettre par l’illusion de la protection : « résilions-nous ! »

La seconde phase de politique de contrôle des flux s’est traduite par la mobilisation d’outils conceptuels, et principalement celui de la résilience. Le titre du Livre blanc du ministère de l’enseignement et de la recherche japonais 2012 annonçait la couleur : « Toward a robust and resilient society ». Les budgets de recherche se sont alors orientés vers l’étude et la mise en œuvre politique de ce concept dans les domaines les plus variés. Anglicisme provenant du terme resiliency, cette notion, dans le domaine des sciences est d’abord utilisée en physique des matériaux pour décrire l’élasticité d’un corps qui aurait la capacité de retrouver sa forme initiale après avoir accusé un choc. Emmy Wermer a introduit cette notion en psychologie, via l’identification de facteurs qui auraient aidé certains enfants à surmonter leurs traumatismes. Boris Cyrulnick a répandu ce concept en France. Les cindyniques, sciences qui traitent des catastrophes, utilisent aujourd’hui ce concept afin de déterminer des modèles qui permettraient à nos villes de résister aux périls. Reconnaissant sa vulnérabilité face aux aléas, la ville serait dans la nécessité d’adopter un caractère résilient afin de pouvoir di-gérer les multiples risques naturels ou humains[13]. Dans le cas présent, tous les outils sont mobilisés et c’est un doux mélange des approches développées concernant la résilience psychologique, écologique, urbaine et tant d’autres encore, qui sont bravées afin de suggérer l’abandon de la fuite à ceux qui obéiraient encore à leur instinct primaire d’angoisse face aux dangers. Parler de résilience en cas de catastrophe nucléaire, c’est néanmoins faire fi du fait que la peur moteur de comportements de protection est parfois salutaire.

Utiliser la résilience urbaine comme outil de gestion des catastrophes pose problème. Le décalage est accru entre le territoire et les producteurs de l’espace, l’être est absent des explications, qui prennent la ville comme objet, mais également comme sujet au sens d’être vivant et autonome, qu’il faudrait ou supporter, ou tenter de soigner sans considérer qu’elle n’est que chose, simple produit construit des humains. Le problème essentiel que cela engendre est, là aussi, une déresponsabilisation[14] des conséquences de l’action de l’être humain sur son environnement. Cela entraine l’oblitération de l’être comme acteur de production et de gestion des espaces, en tant qu’ être vivant dans ces territoires, et anéantit de fait l’inter-action entre le lieux de vie, le milieu, ses habitants, ses producteurs et ses gestionnaires, ces trois dernières catégories pouvant être confondues. Ainsi, un expert de l’université de Fukushima en charge de la protection contre les catastrophes, évoquait lors d’un entretien effectué en juin 2014, la bonne résilience des japonais en cas de tremblement de terre. Ses propos étaient schématisés sur une diapositive enseignant la bonne équation : sur une balance se trouvait d’un côté un rond lourd représentant la résilience, et de l’autre un rond lèger figurant la catastrophe. Selon cette représentation, plus la résilience est lourde et plus les effets de la catastrophe seraient légers. Alors que je lui demandais ce que cela signifiait concrètement pour lui, il me répond embarrassé par le fait que trois jours avant notre entrevue, un tremblement de terre de magnitude 4 avait eu raison de ces concepts : « pour nous, maintenant, il s’agit d’élargir les routes afin que les gens puissent fuire et que les encombrements de 2011 ne se reproduisent pas en cas d’une nouvelle catastrophe car nous les réinstallons au pied d’une centrale nucléaire encore instable». La nécessité de réduire la distance présente grandissante entre la science et la conscience ne pouvait trouver d’exemple plus manifeste.

De la résilience à la communication du risque

Le troisième stade de contrôle des mouvements de population a recours au domaine de la communication sur le risque. Chaque année est un pas supplémentaire vers une plus grande abstraction. L’Etat n’a de cesse d’appeler au retour, arguant la souffrance psychologique des réfugiés générée par l’éloignement de leur pays natal[15]. Selon les experts de l’université médicale de Fukushima et de l’AIEA qui se sont rassemblés le 24 novembre 2013 pour une conférence internationale sur la question, les troubles nerveux observés, notamment chez les habitants des cités de logements provisoires ou des résidants des zones « perçues » comme contaminées proviendraient entre autre, d’un surplus de protection. Le Pr Hirofumi MASHIKO, neuropsychiatre au département de médecine de l’université de Fukushima, explique ainsi que le port du masque, les restrictions diverses liées à l’utilisation des cours d’écoles, des piscines, à la consommation de la nourriture, etc. seraient autant de mesures stressantes à l’origine de désordres psychiques, notamment chez les personnes présentant des prédispositions aux troubles mentaux. A aucun moment, il n’a été mentionné l’éventualité que ces dépressions puissent être la conséquence de l’impossibilité de pouvoir quitter les zones contaminées.

Afin de faire passer le message auprès des premiers concernés et de regagner la confiance des citoyens, une véritable stratégie de communication est adoptée soutenue par un budget spécifique pour l’année 2014 de plus de deux millions d’euros.[16]

Cette politique agressive vise à « éduquer » aux risques sanitaires pour mieux rassurer, notamment via l’organisation de workshop sur la radioactivité et le cancer destinés aux élèves des classes primaires du département de Fukushima[17] ou par la distribution de manuels apprenant à gérer la vie dans un environnement contaminé[18]. Une stratégie d’endoctrinement, au sens propre, ce qui signifie la nécessité qui est et ne peut pas ne pas être, d’accepter la doctrine, s’applique désormais.

Affiche publicitaire pour : qui s’est déroulé le 29 mars 2014 dans une école primaire de Fukushima :[19]

Kids cancer seminar

Because you live in Fukushima there is a necessity of education on cancer !

Le gouvernement inquiet d’une recrudescence des décès

Plus de 1170 décès relatifs à l’explosion de la centrale nucléaire Tepco dai ichi de Fukushima sont comptabilisés au 11 septembre 2014[20]. La population vieillissante relogée dans des logements qui devaient être provisoires, est la première touchée par ce fléau. Le droit au refuge n’ayant pas été accordé en dépit des recommandations faites par le rapporteur aux droits de l’homme de l’ONU Anand Grover suite à sa mission au Japon du 15 au 26 décembre 2012[21], aucun accompagnement financier ne permet à ces habitants le relogement qu’ils escomptaient. Leurs conditions sanitaires se dégradent au fur et à mesure du temps qui passe alors que d’autres décident de partir à leurs frais devant l’instabilité environnementale ingérable au quotidien. La chute dans une spirale de paupérisation touche une partie d’entre eux, alors livrée à la dépression et à l’alcoolisme. Si l’on s’attache à la répartition par ville des décès, les villes de Namie (333 décès), Tomioka (250 décès), Futaba (113 décès) et Ôkuma (106 décès) adjacentes à la centrale dont les fuites d’eau contaminée sont toujours hors de contrôle, comptent parmi leurs habitants 802 décès identifiés comme conséquents de l’explosion de la centrale. 55 d’entre eux ont été enregistrés ces six derniers mois. Le journal Fukushima Minpô, tirait la sonnette d’alarme dans un article du 21 juin 2014[22] rapportant les propos du Ministère de l’intérieur sur le nombre de suicides en recrudescence.

L’accroissement du nombre de cancer de la thyroïde ou la guerre des experts

La multiplication du nombre des cancers de la Thyroïde doit également être prise en compte dans le bilan des conséquences sanitaires de l’explosion de la centrale. Selon la commission d’enquête du département de Fukushima dont les résultats ont été rendus publics le 24 août 2014, 104 enfants de moins de 18 ans, parmi les 300 000 composant l’échantillon, ont été diagnostiqués comme étant atteints d’un cancer de la thyroïde[23].

Les voix d’épidémiologues à l’intérieur comme à l’extérieur du Japon se lèvent pour contrer la position soutenue par les experts de la commission départementale de Fukushima selon laquelle ces cancers ne seraient pas conséquents de l’explosion de la centrale. Ces derniers justifient l’augmentation du nombre de cas de cancer de la thyroïde par l’effet de screening, soit le perfectionnement des outils radiologiques actuels qui, s’ils permettent une détection plus affinée des maladies, empêcheraient par là-même toute comparaison avec les données antérieures. En suivant cette même logique d’une tentative de réconfort morale des habitants, visant à la fois la réouverture de la zone d’évacuation afin d’y reloger la population au plus vite, ainsi que le redémarrage prévu de deux centrales en septembre – octobre 2014, le Ministère de l’environnement soutient dans un rapport rendu public le 17 août 2014 via la chaîne du gouvernement TV-internet[24], 5 journaux nationaux et deux journaux locaux, qu’en deçà de 100 msv/an, aucune conséquence ne serait visible sur la santé[25][26]. Un premier rapport avait déjà été publié par le gouvernement en février 2014, spécifiant la faible dangerosité sanitaire d’un environnement à 100 msv/an comme celui d’un environnement à faible dose[27]. Le Professeur TSUDA Toshihide de l’université d’Okayama, spécialisé en épidémiologie, a remis en cause publiquement point par point l’enquête de l’université Médicale de Fukushima qu’il estime erronée, spécifiant d’une part que le rapport de l’OMS (Organisation Mondiale de la Santé) de 2013[28] notifie clairement une augmentation présente et à venir du nombre de cancer à Fukushima, d’autre part que la position du gouvernement japonais niant les conséquences sanitaires en deçà de 100 msv est une aberration scientifique que peu d’épidémiologues étrangers se risqueraient de prononcer[29]. Le professeur Keith Baverstock, épidémiologue, doyen de l’université de Finlande et ancien membre de l’OMS, dans une lettre ouverte à l’UNSCEAR[30] s’en prend quant à lui aux résultats présentés dans le rapport de l’unscear 2013, en précisant que ce rapport n’est paru que trois ans après l’enquête sur laquelle il est fondé en raison des querelles entre les membres qui composent la commission. L’un de ces membres, le Dr Wolfgang Weiss, s’était notamment opposé à la publication de ce document qui conclut à la négation d’un accroissement du nombre de cancer en rapport avec l’explosion de la centrale de Fukushima. Néanmoins, le document ne nie pas le fait que l’accident n’est en rien fini, puisque, selon les déclarations de TEPCO (mai 2014), la radioactivité s’échappe toujours de la centrale dans l’océan Pacifique et dans l’air[31].

Un remède aux migrations : la communication

Devant les querelles de certains experts, d’autres, qui émanent néanmoins des mêmes organisations (OMS, IAEA, ICRP[32]) tranchent le débat de façon plus directe. Ce fut le cas lors des deux journées consacrées au 3e Symposium des experts internationaux à Fukushima, organisé par la fondation Sasakawa et l’université Médicale de Fukushima les 8 et 9 septembre 2014. Le titre annonçait le dépassement des querelles épidémiologiques pour enfin atteindre les sommets prometteurs de la résilience et de la reconstruction : Beyond Radiation and Health Risk – Toward Resilience and recovery » .

Pour Abel Julio Gonzales, Académicien à l’Académie d’Argentine des sciences environnementales et de la mer, qui tout en étant membre de l’UNSCEAR, occupe la fonction de membre à la commission sur les normes sécuritaires de l’IAEA, tout est une question de communication. Après avoir répété à maintes reprises que la protection a un coût et que le refuge ou la migration d’une partie de la population ne pouvait être un but, celui-ci souhaite revenir sur les mots. La peur des habitants serait notamment due, selon lui, au terme « contamination » qui, référant à la pathologie, accable l’irradiation d’une image négative, alors que les radiations nous viennent également du soleil. Idée reprise par Emilie Van Deveter (OMS) qui propose l’organisation de workshop sur l’irradiation au même titre que sur le soleil, afin d’enseigner les connaissances de base sur la question aux enfants d’écoles primaires. « Quoiqu’il en soit, conclue-t-elle, nous devons gagner le pari du coût-bénéfice ». Pour ce faire et afin de stopper l’hémorragie de population constatée, créer un sentiment de sécurité est désormais la tâche que se donne Jacques Lochard de l’ICRP, notamment « en faisant accepter aux habitants ce nouvel élément qui fera désormais parti de leur quotidien : la contamination ». Tous s’accordent à dire qu’il n’y a pas suffisamment de données afin d’évaluer la contamination interne de la population, mais quoiqu’il en soit, cela ne semble pas être au sein des préoccupations. Selon J. Lochard (ICRP), il ne s’agit pas de fixer un seuil, mais de « redonner confiance aux gens en cassant le processus de fuite qui proviendrait d’archétypes comme Tchernobyl par les mesures individuelles, et permettre ainsi l’auto-gestion du quotidien dans un environnement contaminé ». Il reprend pour se faire, les méthodes proposées par un membre du Ministère de la Santé israëlien, M. Ishay OSTFELD, un des participants du second symposium organisé par l’université médicale de Fukushima et l’IAEA du 21 au 24 novembre 2013. Comme le rappelait M. Ostfeld, « Israel generally uses as a model for its medical response to terror, thus his experience may also serve in the field of radiation terror. »[33]. Celui-ci proposait alors des techniques utilisées en temps de guerre en Israël permettant d’atteindre la résilience, soit l’organisation de petits groupes de résidents convaincuss, disséminés sur le territoire, en charge de rassurer la population avoisinante. Ce travail a été effectué à Fukushima par l’ICRP via les workshop ou dialogues du programme Ethos Fukushima dont le 9e a été organisé en août 2014.

La logique n’est donc pas de mettre en place la protection suite à un désastre via les outils publics de protection sociale, mais de les détourner au service de la décision politique. Il ne s’agit en rien d’un complot, mais de l’application d’une planification de gestion des flux de migrations dans un contexte de catastrophe nucléaire par un Etat qui a opté pour la poursuite de l’industrie nucléaire sur son territoire. On peut néanmoins se demander si les experts fermement assurés de la valeur de leurs postulats psychologiques quant aux possibilités illimitées de manipuler l’opinion ne devraient pas revoir leur copie face aux conséquences macabres qu’un état des lieux nous a permis de mettre en évidence.

Présentation de l’auteur : Cécile ASANUMA-BRICE, spécialisée en sociologie urbaine, est chercheuse associée au Clersé – Univ. Lille 1 et au centre de recherche de la Maison Franco-Japonaise de Tôkyô. Résidente permanente au Japon depuis 2001, auteur de nombreux articles sur la gestion de la catastrophe nucléaire de Fukushima, elle a participé à/ou organisé un grand nombre de conférences sur ce même thème en France comme au Japon. Entre autres références :

- 2014, Co-organisation « Avant et après le désastre de Fukushima : l’impossible échappée ? », colloque et projection de Gambarô (Courage !), film documentaire sur la condition des survivants du désastre nucléaire ; Maison franco-japonaise Tôkyô, 13 juin

- 2014, Co-organisation avec A. Gonon, T. Ribault, Symposium « Making the Right to Health a Reality after the Fukushima Disaster: Obstacles and Perspectives », Doshisha University, Kyoto, 22 mars

- 2013, Fukushima, une démocratie en souffrance, Revue Outre terre-Revue Française de géopolitique, mars.

- 2013, Retour sur Fukushima, Interview France Culture, émission Terre à Terre par Ruth Stegassy, oct.

- 2013, La mémoire de l’oubli, une forme de résistance à la résilience, Après le désastre, réponses commémoratives et culturelles, Université de Tôkyô, 8 Mars.

- 2013, co-organisation colloque « Protéger et soumettre à Fukushima », Maison franco-japonaise Tôkyô, 15-16 octobre.

- 2013, Responsable scientifique, PEPS Mission interdisciplinarité du CNRS (Expertise, controverse et communication entre Science et société) : Les controverses scientifiques face à la responsabilité civique.

- 2012, Co-organisation du colloque Citizen-Scientist International Symposium on radiation protection, 23-24 juin, Inawashiro, Fukushima.

- 2012, Co-responsable scientifique ; Quelle protection humaine en situation de vulnérabilité totale ? – Logement et migration intérieure dans le désastre de Fukushima – dans le cadre du programme Nucléaire, risque et société de la Mission Interdisciplinarité du CNRS.

- 2011, Logement social au Japon : Un bilan après la crise du 11 mars 2011, Revue Urbanisme, nov.

[1] C.ASANUMA-BRICE (2011) : Logement social au Japon : Un bilan après la crise du 11 mars 2011, Revue Urbanisme, Nov.

[2] C.ASANUMA-BRICE et T. RIBAULT: Quelle protection humaine en situation de vulnérabilité totale ? – Logement et migration intérieure dans le désastre de Fukushima – Rapport dans le cadre du programme Nucléaire, risque et société de la Mission Interdisciplinarité du CNRS (2012).

[3] J.-J.DELFOUR (2014) : La condition nucléaire, réflexions sur la situation atomique de l’humanité, Paris, éditions L’échappée.

[4] G.ANDERS (1956), L’obsolescence de l’homme. Sur l’âme à l’époque de la deuxième révolution industrielleParis, Éditions de l’Encyclopédie des Nuisances, réédition 2002.

[5] Entre autre sur le sujet : Le Monde 02/05/2013 : « Le Duo Mitsubishi-Areva va construire quatre réacteurs nucléaires en Turquie ».

Le Parisien (26/10/2013) : “Nucléaire: accord de partenariat entre Areva, Mon-Atom et Mitsubishi”.

[6] Le Monde (16/06/2014) : « Le Japon revient dans la course aux ventes d’armes ».

[7] 15 au 17 décembre 2012, s’est tenue à Fukushima la conférence ministérielle sur la sécurité nucléaire The Fukushima Ministerial Conference on nuclear safety

[8] F. ROMERIO (1994) : Energie, économie, environnement : Le cas de l’électricité en Europe entre passé, présent et futur, ed. Librairie DROZ, Genève.

[9] Entretien réalisé avec T. Ribault à Fukushima en nov. 2013. J. Lochard faisait ici référence au projet ETHOS établi par le CEPN à Tchernobyl en 1986 et à Fukushima en 2012, visant à donner les connaissance de radioprotection à la population vivant dans des territoires contaminés afin de permettre le glissement de responsabilisation que nous évoquons ici, soit l’auto-gestion de sa protection.

[10] C.ASANUMA-BRICE(2013) Fukushima, une démocratie en souffrance, Revue Outre terre-Revue Française de géopolitique, Mars.

[11] Yomiuri, 9 mai 2013 : « Annonce du 7 mai 2013 par le comité de gestion des désastres nucléaires (原子力災害対策本部) de la suppression de la zone de surveillance spéciale jusqu’alors interdite à partir du 28 de ce mois. »

[12] Fukushima Minpô, 23 juin 2014 : 10 ans après l’accident, tout à moins de 20 msv, mise en place de mesures après la décontamination de la zone de retour confus, le gouvernement fait les comptes 事故後10年全て20ミリシーベルト未満 帰還困難区域除染後の線量 国が試算

[13] G. Djament-Tran, M. Reghezza-Zitt (2012) : Résiliences urbaines Les villes face aux catastrophes, ed. Le Manuscrit.

[14] Cette déresponsabilisation provient de la coupure du lien entre les différents acteurs de production et de pratique de la ville nécessaire à toute responsabilisation. Cf. J.Tronto « Le terme de responsabilité (…) renvoie à l’idée de « réponse », c’est à dire à une attitude manifestement rationnelle. »(p.103), in Carol Gilligan, Arlie Hochschild, Joan Tronto (2013) : Contre l’indifférence des privilégiés, éd. Payot.

[15] Fukushima Minpô, 10 oct. 2013 : Le nombre de suicide en augmentation en raison de l’allongement de la période du refuge – dans le département (de Fukushima), et dans les trois départements dévastés « Le ministère de l’intérieur a reconnu une tendance à l’accroissement du nombre de suicides dans le département due à l’accident de la centrale nucléaire Dai ichi et du désastre du Japon de l’Est. Cette année jusque fin août le chiffre s’élève à 15 personnes, l’année dernière, sur une année, on dénombrait 13 personnes, alors que le nombre de suicide était déjà monté à 10 il y a deux ans. Avec 5 fois plus de suicides que dans la préfecture d’ Iwate, le département de Fukushima est celui des trois départements dévastés qui en compte le plus grand nombre. Les spécialistes montrent du doigt la charge nerveuse que représente l’allongement de la période du refuge loin du pays natal. Il est à craindre que la tendance à l’augmentation s’accélère, des mesures d’urgence deviennent nécessaires. »Trad. ABC

[16]平成26年度 原子力関係経費既算要求額、第34回原子力委員会資料第6号。

[17] The 52nd Annual Meeting of Japan Society of clinical Ontology : Kids cancer seminar – Because you live in Fukushima there is a necessity of education on cancer !

[18] NHK, 10 juin 2014, un manuel apprenant à « vivre avec la radioactivité »“放射能と暮らす”ガイド est désormais distribué dans les collectivités.

[19] http://congress.jsco.or.jp/jsco2014/index/page/id/83

[20]「原発関連死、1100人超す 福島、半年で70人増」(le nombre de morts relatifs au nucléaire dépasse les 1100 personnes, avec une augmentation de 70 personnes en 6 mois) Tôkyô Shinbun, 11 sept. 2014

[21] Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Anand Grover, ONU, Mission to Japan (15- 26 November 2012).

[22]「関連死で自殺歯止めかからず 福島県内」(les suicides en rapport avec l’accident ne s’arrêtent plus à l’intérieur du département de Fukushima), Fukushima Minpo, 21 juin 2014.

[23]「甲状腺がん、疑い含め104人 福島の子供30万人調査」(cancer de la thyroïde, 104 personnes, enquête sur 300 000 enfants de Fukushima), Asahi, 24 août 2014.

[24] Dr. Keiichi Nakagawa (Associate Professor, Tokyo University Hospital)

http://nettv.gov-online.go.jp/prg/prg10283.html?t=115&a=1

[25] 2014年8月17日「放射線についての正しい知識を。」という政府広報が、朝日新聞、毎日新聞、読売新聞、産経新聞、日経新聞の大手5紙と、福島民報と福島民友の地方紙2紙に掲載された。Rapport rendu public le 17 août 2014 sous le titre “Pour une connaissance exacte sur la radioactivité” dans cinq journaux nationaux : Asahi, Mainichi, Yomiori, Sankei, Nikkei, et deux journaux locaux : Fukushima Minpô et Fukushima Minyû.

[27] http://www.reconstruction.go.jp/topics/main-cat1/sub-cat1-1/20140218_basic_information_all.pdf

[28] WHO, Health Risk Assessment, 2013.

[29] 津田敏秀、「100msvをめぐって繰り返される誤解を招く表現」、科学、岩波、2014年5月、p.534-530. TSUDA Toshihide, « Autour des 100 msv, sur les expressions qui multiplient les malentendus » Revue Science, Iwanami, Mai 2014, p. 534-540.

[30] Keith Baverstock, « 2013 Unscear Report on Fukushima : a critical appraisal », datée du 24 août 2014.

[32] OMS =Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, IAEA = International Atomic Energy Agency, ICRP = International Commission on Radiological Protection.

[33] Conference Program, International Academic Conference : Radiation, Health, and Society : Post – Fukushima Implications for Health Professional Education, 21-24 nov. 2013, p.79.

Beyond reality – or – An illusory ideal: a pro-nuclear state’s management of migratory flows in a nuclear catastrophe

Cécile Asanuma-Brice

http://japanfocus.org/-C__cile-Asanuma_Brice/4221

Three years have passed since the earthquake and consequent tsunami of March 11, 2011, which led to the explosion of a nuclear power plant in Northeastern Japan. Since then, a central concern in managing the damage is how to handle the relocation of people displaced by the destruction of the earthquake-driven tsunami and the dangers of radiation. In December of that year, we wrote up a precise assessment of the damage caused to the housing sector, the system for rehousing victims of the tsunami, and also the nuclear contamination that has spread widely in part of the Fukushima region and neighboring districts.[1] The government reported the existence of 160,000 displaced persons, of whom 100,000 came from within the prefecture and 60,000 outside of it. Since the government adopted a policy favoring the return of the displaced to their home districts, which are still heavily contaminated, the official estimate today is 140,000 refugees: 100,000 within the prefecture and 40,000 outside it. However, these official figures are the fruit of an extremely restrictive registration system, to which a not insignificant number of inhabitants have refused to submit.[2] The displaced population is in fact appreciably greater than the official statistics would have us believe. What is the situation of nuclear refugees in Japan today? What local policies have been put in place to protect the inhabitants during these three years, as the government sought to manage a disaster of global proportions? What are the motivations of the authorities in seeking to compel the population to return to zones that are still partly contaminated, despite the ongoing risks and in the absence of any request to return? These are a few issues that I will seek to clarify in this paper.

The stakes of the catastrophe

By “catastrophe”, I refer to what Jean-Jacques Delfour[3] has defined as “the normal effects of a series of real causes and the exposure of that series, that is, the negligence, minimizations, circumventions, and refusal to consider the risks created.” It is essential, when considering a government’s management of migratory flows and the choices it makes, to understand both the relevant domestic and international politics. Moreover, among the greatest paradoxes that have followed the catastrophe in question, is the multiplication of international agreements concerning nuclear energy between France and Japan (notably between Areva and Mitsubishi) for the construction of new nuclear plants and the operation of new uranium mines,[4] particularly in Asia. Additionally, though perhaps a coincidence, is the Mitsubishi Group’s first participation in Eurosatory, the world’s largest armament trade show, in June 2014.[5]

In a preparatory phase, the Ministerial Conference on Nuclear Safety was held in Fukushima in December 2012 by the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency), bringing together representatives of countries all over the world, where they resolved to develop nuclear plants that would henceforth be secure and without danger. In the same year as the Fukushima triple disaster, the political decision was made to pursue and develop nuclear energy, placing a premium on the quickest possible return to normalcy at the least cost. The tools devised by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) for radioprotection, based on “concepts of collective doses and on cost-benefit analyses” are used as a foundation for calculating profitability in situations of risk. For the ICRP, the management of risk is guided by an equation, which assigns an economic value to human life, and from which the cost of protecting that life may be calculated, thus determining the cost-effectiveness of providing that protection.[6] As Jacques Lochard, a member of the Main Commission of the ICRP and director of CEPN (Centre d’étude sur l’Evaluation de la Protection dans le domaine Nucléaire), stated during an interview with the author in November 2013, “Ethos is never without Thanatos”.[7] The key is to know on which side one wants to tip the scale. Assigning a monetary value to human life certainly provides an extreme example of the tendency in our society toward the objectification of human beings, one fully consistent with the present Abe Shinzo government’s attempts to reopen Japan’s closed nuclear facilities.

The politics of controlling population flows in post-3/11 Japan can be divided into three phases, in accordance with the directives formulated by the government in its annual priority plans.

A Management policy to reverse migratory flows

The first stage was set in motion during the year following the catastrophe. The need to respond was urgent; this was primarily done by opening up the stock of vacant public housing throughout Japan and constructing new temporary barracks-like emergency housing, both made available free of charge, to take in the victims. While this measure constituted a form of emergency relief, within Fukushima Prefecture, attempts to reassure the population created rather an illusion of protection: temporary lodgings were built partly in contaminated areas, radiation measuring stations installed were tampered with, and decontamination efforts were largely ineffective.

The distribution of emergency temporary housing vs. the distribution of radiation

Map created by Cécile Asanuma-Brice

Map created by Cécile Asanuma-Brice

Temporary lodgings in Aizuwakamatsu, May 2013. Photos Cécile Asanuma-Brice

Temporary lodgings in Aizuwakamatsu, May 2013. Photos Cécile Asanuma-Brice

The end of 2012 marked the first official call for the refugees to return home, coinciding with termination of the national program to provide vacant public housing throughout the country rent-free, but leaving the choice of requiring refugees to leave public housing in the hands of the authorities in local communities. This is one of the fundamental points characterizing official management of the disaster: the transfer of responsibility from the central to local governments, and frequently from local government to the victims. Shifting responsibility from the central government to local communities is the first step in this process. This translates into a considerable delay in reconstruction projects, since the generally impoverished local communities concerned lack the financial means and resources to manage these problems. In short, while not actually reconstructing anything, luring refugees home with the claim of a fictitious reconstruction guarantees reduction of costs to the center compared to the expense of actual reconstruction. Above all, the national authorities, who are working to resettle the inhabitants within the prefecture in order to better monitor them statistically and scientifically, are unwilling to invest in the protection of people they view as the damned and disposable. Why invest in public housing in a region that is already depopulated and destined to become even more so?

The second stage in state abandonment of its responsibilities to victims consists of transferring responsibility to individuals who have been forced to adapt their lives to a contaminated environment or are faced with choosing exile under conditions of extreme adversity. Specifically, the government offered no financial or material assistance to those who wished to seek refuge or rebuild their lives elsewhere. An aggressive public relations campaign was devised to discourage exile or resettlement elsewhere by widely disseminating images depicting how onerous it is for Japanese to leave their local areas and ancestral . While leaving one’s home is particularly traumatic for those who have farmed that land all their lives, this feeling is hardly limited to Japanese farm families. A number of people that we interviewed during our research expressed the desire to leave despite their attachment to the land, only to be confronted with the impossibility of this course in the absence of government financial support.[8]

Reopening to better heal

The policy calling for the displaced to return home resulted in reopening part of the restricted zone at the end of May 2013. This policy of shrinking the restricted zone has significant financial implications for evacuees who are now eligible for less compensation from the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco). So what may be good but undeserved PR for government decontamination efforts is bad news for people who now find their homes declared habitable when in fact that is a fiction since their homes are located in still contaminated ghost towns. In April 2011, the government established an evacuation zone of 20 km around the Fukushima Daiichi plant, comprising the city of Futaba and eight other localities. The entire perimeter was reorganized. The boundaries of the zone open for return following decontamination (避難指示解除準備区域) (meaning areas in which the contamination level was below 20 millisieverts), and the “difficult” return zone (帰還困難区域)(50 millisieverts) were revised to enable reopening of some areas (see map below). The special regulation zone, to which return had not been permitted, comprised of nine localities around the plant, was completely eliminated.[9] A total of 76,420 people were affected by these measures. Sixty-seven percent of them, or 51,360 people, were from the zone in “preparation for cancellation of the evacuation directive” (避難指示解除準備区域). They were permitted to move freely throughout the zone during the day to visit and work on their homes and land, but not to remain over night. The directive was partially cancelled effective August 2014. The restricted residence zone (居住制限両区域), which concerns 25% of inhabitants (19,230 people), allows for free entrance and exit from the zone during the day, but without authorization to work there. The possibility to return to work during the day affects 42% of the population, or 32,130 people. Nonetheless, situations vary within each locality. Supermarkets, medical centers, and other services cannot be reopened, meaning that these reopened areas remain uninhabitable for practical reasons. Nevertheless, part of the towns of Okuma and Futaba have been used as decontamination test zones, with a view toward opening the zone in preparation for cancellation of the evacuation directive.

Map of the state of the evacuation zone on April 1, 2011(left)and June 2014 (right)[10]

For 2011 Map (left): orange represents the evacuation zone; pink, the voluntary evacuation zone; yellow a preparation zone for evacuation in case of emergency.

For 2011 Map (left): orange represents the evacuation zone; pink, the voluntary evacuation zone; yellow a preparation zone for evacuation in case of emergency.

For 2014 Map (right): pink is the “difficult return zone” (more than 50 millisieverts/year), yellow is the limited residence area (20 to 50 msv/y), green is the “preparation for cancellation of the evacuation directive” area (below 20 msv/y).

The town of Tomioka in the zone of limited residence, October 25, 2013. Radiation level at 3 µSv/h.

The town of Tomioka in the zone of limited residence, October 25, 2013. Radiation level at 3 µSv/h.

Subdued by the illusion of protection: Let’s be resilient!

The second phase of the migration control policy was marked by the attempt to mobilize conceptual tools, principally that of resilience. The title of the 2012 white paper of the Japanese Ministry of Education revealed this intention: “Toward a robust and resilient society”. Research budgets were oriented toward the study and implementation of this concept in a variety of fields. In the sciences, the notion of resiliency is used in materials physics to describe the elasticity of a body and its ability to return to its original form after suffering a shock. Emmy Werner introduced this idea in psychology, via the identification of factors that could help certain children to overcome . Boris Cyrulnick spread this concept in France. Cindynics, the science of risk management, uses this idea today as a way to frame models that might allow cities to better resistdangers. Recognizing their vulnerability to hazards, cities must adopt a resilient character in order to handle the many risks that confront them, whether natural, man-made or a combination of the two.[11] In the present case, all the tools have been mobilized and a subtle mix of approaches to resilience–psychological, ecological, urban, and many others–developed, so as to counter peoples’ natural instinct for self-preservation. Extolling resilience is also a strategy for shifting responsibility for recovery from the national government to this region of hardscrabble people who have a history of overcoming adversity, turning their virtue into an excuse for the government to do as little as possible. No wonder that locals bristle at the endless praise for their culture of gamanzuyoi (perseverance). Yet, when speaking of resilience in the case of nuclear catastrophe, one should nevertheless recognize that fear, as an engine of human behavior, can sometimes play a salutary role.

Relying on urban resilience as a tool for managing catastrophe is problematic. The disconnect between territory and the “producers of urban space” is increased because the individual is absent from analyses that treat the city as an object, but also as a subject–i.e., a living, autonomous being, which one must either support or attempt to care for, without considering that it is just a thing, a simple product constructed by humans. The essential problem that this creates is, again, irresponsibility[12] regarding the consequences of human activity on the environment. This leads to the nullification of the individual as an actor in the production and management of space, as a person living in these areas, and de facto destroys the interaction between a place to live, its setting, its inhabitants, its producers, and its administrators (with the last three categories possibly overlapping).

An expert at Fukushima University in charge of protection against catastrophes, interviewed in June 2014, spoke of the great resilience of the Japanese during earthquakes. His remarks were illustrated by a slide presenting a simple equation: a scale is shown with, on one side, a heavy circle representing resilience and, on the other, a light circle representing catastrophe. In this schema, the heavier the resilience, the lighter the effects of the catastrophe. When I asked what that meant to him in concrete terms, he answered uncomfortably that three days earlier a magnitude-4 earthquake had negated these concepts: “for us, now, it’s about enlarging the roads, so that people can flee and the blockages of 2011 don’t reoccur in the case of a new catastrophe, [which should be considered] since we are relocating them at the foot of a nuclear plant that is still unstable.” The need to reduce the present, and growing, distance between science and conscience could not find a clearer example.

From resilience to the communication of risk

The third stage of controlling population flows involves risk communication. Each year is another step towards an ever greater abstraction. The State has never stopped calling for refugees to return home, citing the psychological suffering caused by their separation from their native land and downplaying the physical and hereditary risk of radiation.[13] According to experts at Fukushima Medical University and at the IAEA, who gathered on November 24, 2013 for an international conference, the psychological disorders observed, notably among inhabitants of the temporary housing estates or residents of zones “perceived” as contaminated, stem from, among other things, over protection. Professor Hirofumi Mashiko, a neuropsychiatrist in the medical department of Fukushima University, explains that the need to wear a facemask, the various restrictions on using playgrounds and pools and on the consumption of food, etc., are stress factors and could be at the root of psychological disorders, especially among people who may be predisposed to mental illness. At no time did he mention the possibility that such depression might stem from the inability to leave the contaminated zones.

In order to get the message out to those most concerned and to regain the trust of the citizenry, a communication strategy was adopted supported by a budget target for 2014 of more than two million euros.[14] This aggressive policy aims to reassure the public by teaching it that the health risks of radiation are minimal while psychological risks are severe, particularly through the organization of workshops on radiation and cancer designed for primary school classes in Fukushima Prefecture[15] and by distributing manuals on managing life in a contaminated environment.[16] A strategy of indoctrination, in the literal sense, has been in place from this point on, affirming the absolute necessity to accept the doctrine.

[photo][17]

Upbeat publicity poster for a March 29, 2014 event at a Fukushima primary school:

Upbeat publicity poster for a March 29, 2014 event at a Fukushima primary school:

Kids cancer seminar

Because you live in Fukushima there is a necessity for education about cancer!

Government anxiety over a resurgence of deaths

There were more than 1,170 deaths (関連死) related to the explosion at the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant as of September 11, 2014.[18] This includes deaths among those who fled the explosion and contamination, and emergency workers at Daiichi. The first to be touched by this phenomenon were the elderly relocated to “temporary” housing; their health has gradually deteriorated as time has passed. Because the Japanese government did not accord the right to refuge to people located in contaminated areas, despite the recommendations made in 2012 by Anand Grover, the UN Special Rapporteur for human rights,[19] no financial support is available for nuclear refugees seeking to relocate. Those who can, leave at their own expense. “Those” refers to people who are not in the officially designated evacuation areas described above who decide to take refuge. They are considered “voluntary refugees” and thus the Government provides no financial assistance. The descent into a spiral of pauperization often leads to depression and alcoholism, and, in extreme cases, suicide. If we focus on the distribution of Fukushima nuclear disaster related deaths by locality, the towns of Namie (333 deaths), Tomioka (250 deaths), Futaba (113 deaths), and Ōkuma (106 deaths), which are adjacent to the plant–where leakage of contaminated water is still not under control–together account for 802 deaths identified as resulting from nuclear disaster; fifty-five these occurred within the six months from January to June 2014, indicating that the crisis persists despite government propaganda that it is under control. The newspaper Fukushima Minpō sounded the alarm in an article on June 21, 2014[20] reporting the remarks of the Minister of Internal Affairs and communications on the rising number of suicides.

Increased incidence of thyroid cancer, or the battle of the experts

The proliferation of the number of cases of thyroid cancer must also be taken into account in assessing the health consequences of the nuclear accident. According to results made public on August 24, 2014 by the Fukushima Prefecture board of inquiry, 104 of 300,000 children under age eighteen were diagnosed as having thyroid cancer.[21] The Japan Association of Clinical Regents (JACRI-日本臨床検査薬協会), estimates that the natural rate of thyroid cancer in Japan is 1-3 persons per million. Epidemiologists, both in Japan and internationally, have challenged the insistence of experts on the Fukushima Prefecture Commission that these cases are not linked to the nuclear disaster. The Commission claims that the rise in the number of cases of thyroid cancer for the last three years is attributable to the “screening” effect, i.e., the comprehensive testing of Fukushima children and advances made in radiological testing which now allow for a much more precise detection of cancer. At the same time, it prevents any meaningful comparison with earlier test results. Keeping to the strategy of providing moral comfort to the populace—with an eye, not only to reopening the evacuation zone so as to rehouse the population as quickly as possible, but also to the scheduled restart of two nuclear plants in September-October 2014—the Minister of the Environment stated in a report made public on August 17, 2014, that below the level of 100 msv/year, there would be no apparent consequences on human health.[22] A previous government report published in February 2014 designated the low risk to health of an environment with 100 msv/year as that of a low-dose environment.[23] Professor Tsuda Toshihide of Okayama University, who specializes in epidemiology, publicly contested point by point a study by the Fukushima Medical University, which he found erroneous; to support his case, he cited the 2013 WHO (World Health Organization) report,[24] which clearly warns of an increase, both at present and still to come, in the number of cancer cases in Fukushima; conversely, he criticizes the position of the Japanese government’s denial of the health risks below 100 msv, noting that it is a position that few foreign epidemiologists would support.[25] Epidemiologist Keith Baverstock, a docent at the University of Eastern Finland and former member of the WHO, criticized the results presented in the 2013 report by UNSCEAR (United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation); in an open letter to UNSCEAR, he pointed out that the report did not come out until three years after the study it was based upon due to disagreements between members of the commission. One of these members, Dr. Wolfgang Weiss, particularly opposed publication of this document, as it rejected a connection between an increase in cancer incidence and the plumes of radiation released by the explosions at Fukushima Daiichi. However, the report does not deny the fact that the effects of the accident are in no way over, since, as TEPCO acknowledges in statements in May 2014, large quantities of radiation are still escaping from the plant, both into the air and into the Pacific Ocean.[26]

A remedy for migration: communication

In the face of quarrels among experts, there have been efforts by others from the same organizations (WHO, IAEA, ICRP) to ‘rebrand’ the issues through aggressive marketing of reassuring messages. This was the case during the two days of the 3rd International Expert Symposium in Fukushima, organized by the Sasakawa Foundation and the Fukushima Medical University on September 8-9, 2014. Its title explicitly heralded a desire to transcend the epidemiological disputes to reach the promising heights of resilience and reconstruction: “Beyond Radiation and Health Risk – Toward Resilience and Recovery”.

For Abel Julio Gonzales, Academician at the Argentine Academies of Environmental Sciences and of the Sea, as well as a member of UNSCEAR and of the IAEA Commission on Safety Standards, everything is a question of communication. After having repeated many times that protection has a price and that the migration of some of the population should not be a goal, he asserted that residents’ fears are due primarily to the term “contamination”, which, given its association with pathology, has saddled irradiation with a purely negative image, despite the fact that we also receive radiation from the sun. This idea was picked up by Emilie Van Deveter (WHO), who proposed organizing a workshop on radiation exposure, including that from the sun, so as to teach primary school students basic knowledge of the subject. “In any event,” she concludes, “we must win the cost-benefit challenge.” In order to do so, and to manage the anxieties of the affected population, Jacques Lochard of the ICRP has taken on the task of creating a sense of security, in particular “by persuading the inhabitants to accept this new element that will from now on be a part of their everyday life: contamination.” Everyone is agreed that there is not sufficient data to evaluate the internal contamination of the populace, but be that as it may, this does not seem to be at the heart of their concerns. According to Lochard, it is not a matter of establishing a threshold, but rather of restoring people’s confidence by disrupting the recourse to flight–which comes from archetypes like Chernobyl–through individual measures, and thus allowing for self-determination over life in a contaminated environment.” To do so, he has adopted the methods proposed by Ishay Ostfeld of the Israeli Ministry of Health, at the second symposium organized by Fukushima Medical University and the IAEA on November 21-24, 2013. Mr. Ostfeld explained that “the Israeli experience in responding to conventional terror demonstrates significantly more psychological than physical trauma victims… thus this experience may also serve in the field of radiation terror.”[27] He therefore suggested the use of techniques developed in Israel during war to achieve resilience, such as the organization of small groups of committed residents, spread throughout the affected territory, who would take charge of reassuring the neighboring populace. This work has been undertaken in Fukushima by the ICRP, through workshops and seminars in concert with Ethos Fukushima, the 9th edition of which was held in August 2014.

Continuing with the war analogy, the Battle of Fukushima is thus not about using the public policy tools of post-disaster social protection to provide help for displaced people, but requires diverting these resources to serve the political agenda of normalizing the consequences of this nuclear disaster to facilitate nuclear reactor restarts. This is in no way a government conspiracy, they insist. Rather, it is a plan for managing migratory flows of people in the face of a nuclear disaster, in this instance one in which a state (Japan) has opted to maintain its nuclear industry. One can nonetheless wonder if the experts, despite firmly held assumptions about the unlimited possibilities for manipulating public opinion, should not reconsider their position, given the macabre implications.

Cécile Asanuma-Brice, an urban sociologist, is an associate researcher at Clersé–University of Lille 1 and at the research center of the Maison Franco-Japonaise in Tokyo. A permanent resident of Japan since 2001, she is the author of numerous journal and newspaper articles on the handling of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, including:

(2014 forthcoming) “De la vulnérabilité à la résilience, réflexions sur la protection en cas de désastre extrême : Le cas de la gestion des conséquences de l’explosion d’une centrale nucléaire à Fukushima,” Revue Raison Publique, “Au-delà du risque Care, capacités et résistance en situation de désastre,” co-dir° Sandra Laugier, Solange Chavel, Marie Gaille.

(Sept. 2014) Mobilisations, controverse et recueil des données à Fukushima, La Lettre de l’INSHS, CNRS,

(March, 2013) Fukushima, une démocratie en souffrance, Revue Outre terre-Revue Française de géopolitique

(June 2012) Les politiques publiques du logement face à la catastrophe du 11 mars, in C. Lévy, T. Ribault, numéro spécial de la revue EBISU n°47 de la Maison franco-japonaise, Catastrophe du 11 mars 2011, désastre de Fukushima – Fractures et émergences.

She was a co-organizer of the colloquium « Protéger et soumettre à Fukushima », Maison franco-japonaise Tōkyō, October 15-16, 2013. (2013) and Faut-il se résigner à la résilience ? L’assignation à demeure d’une population en péril, Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, Paris, 29 mars.

Newspaper articles include (2014) « La légende Fukushima », Libération, septembre, http://www.liberation.fr/terre/2014/09/23/la-legende-fukushima_1106968

and (2013) « Crime d’Etat » à Fukushima : « L’unique solution est la fuite », Le Nouvel Observateur-Rue 89, juillet, with T. Ribault.

Recommended citation: Cécile Asanuma-Brice, http://www.rue89.com/2013/07/03/crime-detat-a-fukushima-lunique-solution-est-fuite-243864

[1] C. ASANUMA-BRICE (2011): Logement social au Japon : Un bilan après la crise du 11 mars 2011, Revue Urbanisme, Nov.

[2] C. ASANUMA-BRICE et T. RIBAULT (2012): Quelle protection humaine en situation de vulnérabilité totale? – Logement et migration intérieure dans le désastre de Fukushima – Report within the program Nucléaire, risque et société of the Interdisciplinarity Project of the CNRS.

[3] J.-J. Delfour (2014) : La condition nucléaire, réflexions sur la situation atomique de l’humanité, Paris, éditions L’échappée.

[4] Among others on the subject: Le Monde (02/05/2013) : « Le Duo Mitsubishi-Areva va construire quatre réacteurs nucléaires en Turquie »; Le Parisien (26/10/2013) : “Nucléaire: accord de partenariat entre Areva, Mon-Atom et Mitsubishi”.

[5] Le Monde (16/06/2014): « Le Japon revient dans la course aux ventes d’armes ».

[6] F. Romario (1994): Energie, économie, environnement : Le cas de l’électricité en Europe entre passé, présent et futur, ed. Librairie DROZ, Genève.

[7] Interview conducted with T. Ribault in Fukushima in November 2013. Lochard was referring here to the ETHOS project established by the CEPN in Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2012, with the aim of providing the population living in contaminated areas with knowledge of radioactivity protection, so as to shift responsibility for their protection from the state and/or TEPCO to local people. We may call this the self-management of its protection.

[8] C. ASANUMA-BRICE (2013) Fukushima, une démocratie en souffrance, Revue Outre terre-Revue Française de géopolitique, Mars.

[9] Yomiuri, 9 mai 2013: “Announcement on May 7, 2013 by the nuclear disaster countermeasures headquarters [joint measures council for nuclear disaster] (原子力災害対策本部) of the elimination of the previously off-limits special surveillance zone starting on the 28th of this month. »

[10] Fukushima Minpō, 23 juin 2014: 10 years after the accident, the government takes stock, with measures established following the decontamination of the difficult return zone, at less than 20 msv 事故後10年全て20ミリシーベルト未満 帰還困難区域除染後の線量 国が試算

[11] G. DJAMENT-TRAN, M. REGHEZZA-ZITT (2012) : Résiliences urbaines Les villes face aux catastrophes, ed. Le Manuscrit.

[12] This irresponsibility is a product of cutting the link between the different actors of the city’s production and practice that is necessary for effective responsibility. Cf. J.TRONTO « The term responsibility (…) refers to the idea of a « response », that is to say to a clearly rational attitude. » (p.103), in Carol Gilligan, Arlie Hochschild, Joan TRONTO (2013) : Contre l’indifférence des privilégiés, éd. Payot.